Las Adelitas Mariachi Band performed a couple of days ago at The British Museum. Tamara and I went there for a break after a long appointment, and we had no idea anyone was performing.

In fact it is the first performance of any kind in the Museum atrium that I recall.

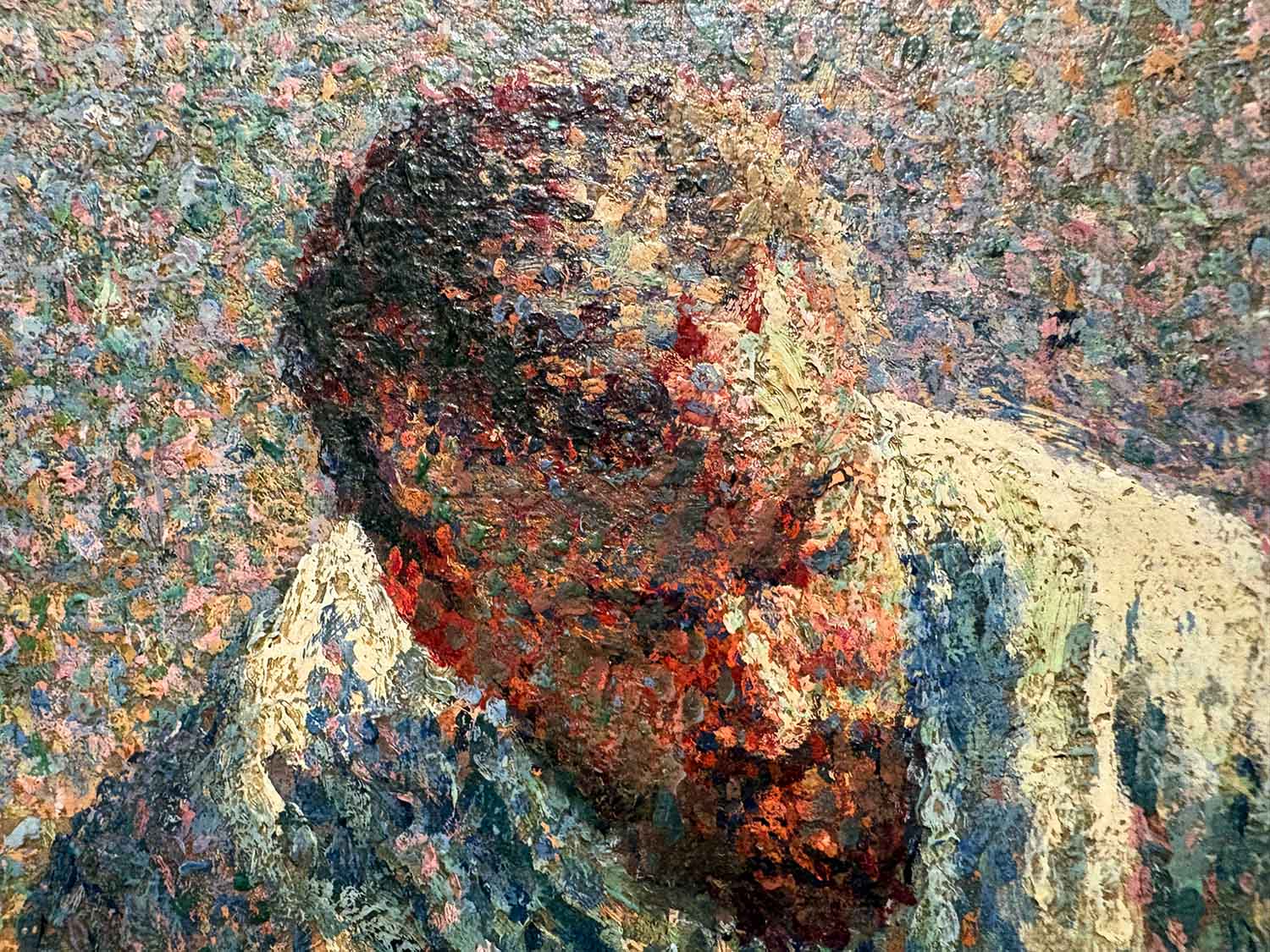

I had my little Ricoh GRIII with me, and I took some shots before the performance started and more photos after it end. This first shot is after the performance, when the band members were chatting with the audience.

The band’s sound equipment was off to the side. In this next photo the equipment is in the direction the man with the jeans is looking.

And appeared there was some friction in getting the sound right.

I don’t think it was helped by the huge clattery space that is the atrium of the museum, and I guess no one ever thought of designing it to be conducive to music, or performance generally.

The close-up crop of the photo above it is an example of what I like in photography – that you get to see the personalities of people and their reactions to events.

The woman with the short hair sang first, and then the shorter woman next to her sang a torch song ballad full of passion and seriousness. She was remarkable.

And then the photo below is after the performance with the band standing again with the supervisor who I guess is from the British Museum.

Las Adelitas

Adelita is a nickname given to women who fought during Mexico’s Revolutionary War.

The name came from a revolutionary ballad inspired by Adela Velarde Pérez, a revolutionary from Chihuahua.

Mexico’s Revolutionary War lasted from 1910 to 1920, and the result was huge social change. The first to fall was the dictator Porfirio Díaz, who was kicked out and exiled in 1911.

Although Mexico had a constitution that dated back to 1857, and a Congress and a judiciary, the reality was the Diaz ruled it all.

And he was in power for a long time – from 1876 – and he brought stability and economic growth; encouraged foreign investment, modernised the railways, the telegraph, and industry generally, and opened the economy to international markets.

So with all that progress, what was the failure that led to his exile?

Partly it was that although Diaz himself was mestizo and partially Indigenous, he pushed an image of himself that emulated European cultural ideals. ‘Whitening’ was an official government policy, and Diaz pushed economic policies on the same model.

And as in many revolutions, only a minority had felt the benefits. Rural peasants and Indigenous communities lost their communal land to private estates. Workers in the city were poorly paid.

Out of the revolution came land reform with the breakup of the big estates, and new labour laws, with rights enshrined in the new constitution of 1917.

And the cost? Historians estimate that between one and two million people died in the war.

Having travelled in Central and South America I have some little insight into how a home-grown liberator can be subsequently viewed as no liberator at all. The Spanish were effectively driven out of Mexico in 1821, but for many people the system did not change.

When I travelled in South America in the early nineties, in different countries I saw people wearing badges with “quinientos años de resistencia” – five hundred years of resistance. Their view was that when the Spanish were kicked out it only succeeded in replacing ‘foreign’ oppressors for home-grown oppressors. In that view, Simon Bolivar was not a liberator but simply the new boss, same as the old boss.

Look at the history of almost any of the countries in South America to see how perilous any kind of stability has been.