Perspective compression (also known as lens compression) is a visual effect in photography.

You already know about compression because you know that when you look at traffic in the far distance, the cars seem to be all bunched up. When they get close you see there is more distance between the cars.

So perspective compression means faraway objects appear closer together – bunched up – than when viewed close up with the naked eye.

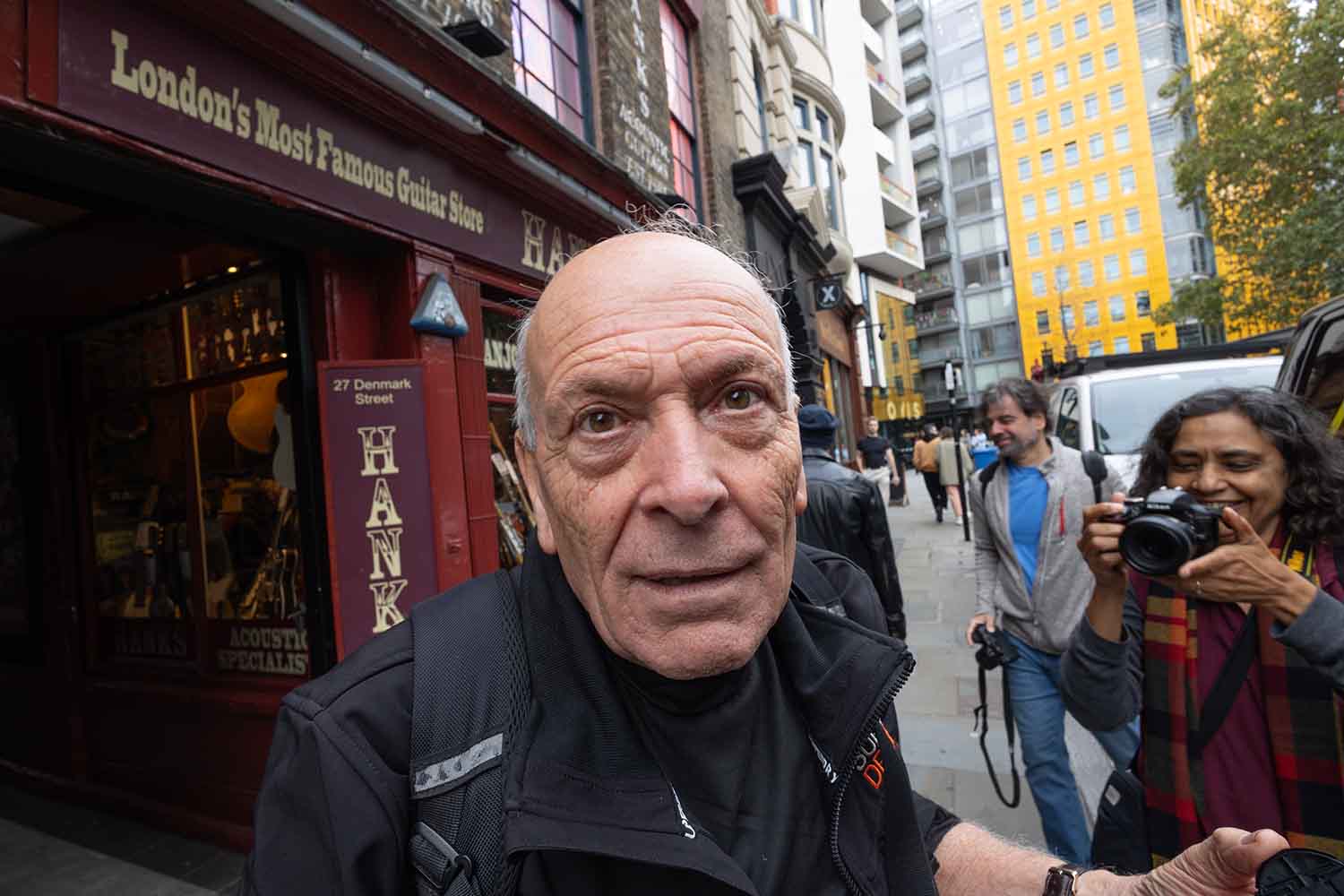

And it is the same with camera lenses, and we see the opposite effect when the camera lens is very near to an object in the foreground and the object is round like a person’s head.

The middle of the face will appear bigger and nearer than the outer parts of the face that are further from centre the lens.

That stretching is the opposite of perspective compression or lens compression. And it is because the lens is very near the subject.

People Versus Animals

Lack of compression is not flattering in people but we don’t mind it is animals because we don’t have a strict idea of what the relative size of nose and ears and the curve of the face should be.

Focal Length

So more distance equals more perspective compression. So how, if at all, is perspective compression or lens compression affected by the focal length of a lens?

Long focal lengths lenses show more compression but it is not because of the focal length in itself.

It’s because to frame the subject the lens is going to be further away from the subject.

To repeat, perspective compression is simply a function of the distance between the camera and the subject, and it is not directly because of the focal length. But focal length influences how far back you need to stand to frame the subject, which in turn affects compression.

Using Perspective Compression

If you want perspective compression – for example to make a face look more attractive – shoot from a longer distance, which means using a longer focal length lens.

Typically, for a full frame lens that means shooting with a focal length in the region 135mm to 200mm.

With an APS-C sensor you would get the equivalent compression by using a lens of between say 85mm and 135mm.

If you were to use a 16mm lens like I did for the shot of the man’s face, you would have to get very near to your subject (like I did) for the face to fill the frame. The nose would appear big in the face and the face would appear narrow as the distance increases around the sides of the face.

So to make a face look as attractive as possible, don’t use a short focal length lens.

But suppose you don’t have a long lens. What then?

Cropping

What about cropping the image after you have taken it?

For example, a photo shot with a camera with a full-frame equivalent 35mm lens can be cropped to the field of view equivalent of a longer focal length lens.

How Much Can You Crop?

The limit to how much you can crop is how many pixels are left after cropping. With too few pixels left, the image will be poor quality.

Starting with a 24MP sensor like with the Ricoh doesn’t leave many pixels after cropping heavily.

What About More Megapixels?

A higher megapixel sensor would allow more cropping.

For example, the Fujifilm X-T50 has a 40MP sensor, so it will take heavy cropping.

Still, using a longer focal length lens means you don’t need to crop, so you don’t sacrifice any pixels at all. And that is the reason we have long focal length lenses n the first place.

Acuity

Then again, we have to think about the viewer. Acuity is an impression of sharpness and is related to the ability of the human eye to see the sharpness. After all, if the human eye can’t see the difference in acuity between a lower megapixel image and a higher megapixel sensor then there is no difference in practical terms, and those extra pixels are just wasted.

To put that in context we have to think about a normal viewing distance. An advertisement plastered on the side of a bus may look good when viewed from across the road. But if we were to go right up to it and look then we would see the coloured dots of which the image is made.

But we don’t stand close to buses or billboards because standing close is not the normal viewing distance. So then we can ‘get away with’ a lower pixel density.

The Future?

We already have 100 megapixel cameras – not specialised instruments – just ordinary cameras you can hold in your hand. The Fuji GFX10OS |I for example weighs less than 900g.

Ten years ago that number of pixels on a sensor was unthinkable.

Twenty years ago the highest megapixel digital camera on the market was the Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II, with approximately 17 megapixels.

It was one of the most sought-after cameras to which professional photographers aspired.

Now my little Ricoh, that I can slip in my pocket, has more megapixels than that top of the range Canon from 20 years ago.

Technology is spinning ever faster and it doesn’t take much imagination to see a time when we will have 1,000 megapixel sensors in cameras.

Then we will be able to use short lenses – perhaps a 28mm like on the Ricoh – and just crop like crazy to zero in on the bit of the photo we want.

There would be so many pixels to start with we would be able to crop to our heart’s content.

Sensor Size

The capability of a sensor to receive a good light signal depends on the physical size of the sensor.

The long side lengths of medium format, full-frame, and APS-C sensors are approximately 43.8mm, 36mm, and 23.5mm respectively. The sensor on the iPhone 16 is just 14.7mm long.

I have an iPhone 16 and it has a 48MP sensor. But the sensor itself is so small that blowing up an image or cropping heavily soon shows the limits of the sensor.

So make high-quality images from a 1,000 MP sensor, the sensor will have to be above a certain physical size, and probably at least as big as a current medium format sensor.

But who knows? A real revolution in the way micro lenses capture light might turn this on its head, just like all the revolutions of the past. It is just 50 years since the very first digital camera, and that had a resolution of 0.01 megapixels and the camera weighed five kilos.

Leave a comment