Baker Street Station

Living in London I have begun to form a clearer picture of how complicated and incredible is the London Underground system.

Imagine a crossroads with, let’s say, five roads leading to it. And imagine buses with routes on those roads with passengers who want to get off one bus and change to another bus.

Obviously, they have to cross from one road to another to make their connection.

Now imagine the crossroads in three dimensions with roads below and above, and escalators and pavements so people can get to the bus stops on other roads.

Now imagine it all underground.

That’s the London Underground at stations that serve more than one line – like Kings Cross, Westminster, Bank, and Baker Street.

Baker Street in the photos at the top here, is an old station and it would not be out of place in a period film about 1940s wartime London. And it would not be out of place in a set from much earlier because Baker Street station opened in 1863, and was one of the original stations on the world’s first underground (metro) line.

The Information board at Baker Street station says that because the trains were powered by steam, there were frequent open-air sections along the track.

Baker Street serves the Hammersmith & City, Central, Jubilee, and Metropolitan lines – and it is a rabbit warren.

The Circle, Hammersmith & City, and Metropolitan lines at Baker Street are the oldest lines. They are what are known as cut-and-cover lines, meaning that the workers who built them dug down from the surface, built the line, and then covered them over. So these lines are just below street level, and are accessed via stairs from the concourse areas.

The Jubilee and Bakerloo lines are deep-level tube lines, accessed via escalators.The Jubilee line platforms can also be reached by lift from the ticket hall at ground level.

I have to make a video of what it is like to get off the Metropolitan Line and go to the train on the Jubilee line. Upstairs, downstairs, along one level then down and up and around and along the platform and then back up again – and all of it looking like a scene that Sherlock Holmes would be at home with.

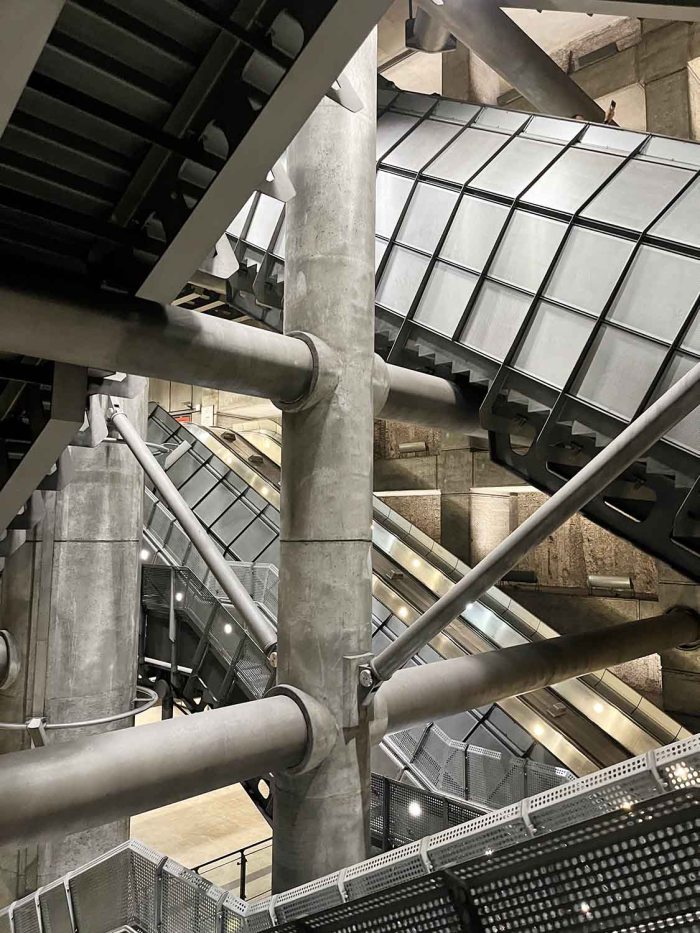

Westminster Station

Westminster Station is modern. But it still obeys the laws of physics and so there are concrete and steel escalators and walkways everywhere.

All of which leads me to what can happen when things go wrong because at any one time there is more than nine tonnes of bodyweight on the escalators and more than six million escalator journeys per day.

The Kings Cross Fire

In early evening of 18 November 1987, a small fire broke out on the London Underground at King’s Cross station.

Investigators worked out that someone dropped a lighted match while they were on one of the escalators.

Underneath the escalators there was decades of accumulated paper wrappers, bits of discarded newspaper, old matches, and other waste mixed with years’ of accumulated grease that kept the machinery of the escalators moving freely.

It was the perfect tinder box and the fire travelled all the way up to ground level under one of the escalators on the Piccadilly line.

Then at about 7:45pm a fireball ripped up through the whole length of the escalator and into the ticket hall.

Some passengers jumped onto another escalator and escaped, but 31 people died, including a senior firefighter who came with his crew to tackle the blaze.

And many others were seriously injured.

Nowadays no one is allowed to smoke in any indoor location anywhere in the country. But in 1987, while smoking on the Underground was officially banned it was tolerated.

It’s easy to forget how people smoked everywhere. I remember sitting on the top floor of the bus coming home from school and being fascinated by working men from the heavy engineering factories sitting in filthy black clothes, wearing a flat cap, and smoking.

After the public inquiry that followed the King’s Cross fire the banning of smoking was strictly enforced everywhere on Kings Cross Station and all other Underground stations. And the wood escalator steps were replaced with metal steps.

In reality, no one needed to tell people to obey the ban. The fire seared into the consciousness of a whole generation. And then a ban on smoking inside at all venues came into effect and people simply stopped smoking in the way they once did.

Summary

The 1988 public enquiry known as the Fennell Report concluded that the fire was caused by a discarded match, probably dropped by a smoker, which ignited accumulated grease, dust and rubbish beneath a wooden escalator at King’s Cross St Pancras station.

London Underground was judged responsible for a systemic failure of management, safety culture and preparedness in tolerating smoking despite official bans, failing to appreciate the fire risk posed by wooden escalators, allowing combustible debris to build up, and lacking adequate staff training for serious fire emergencies., and failing to change methods or learn from previous small fires.

Leave a comment